| A Vienna Style Dark Lager Beer Photograph by Leticia Alaniz © 2012 All Rights Reserved |

Ever since the emergence of "anatomically modern" humans, or Homo sapiens, in Africa around 150,000 years ago, water had been humankind's basic drink. A fluid of primordial importance, no life on Earth can exist without it. But with the switch from the hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a more settled way of life, humans came to rely on a new beverage derived from barley and wheat, the cereal grains that were the first plants to be deliberately cultivated. This drink became central to social, religious, and economic life and was the staple beverage of the earliest civilizations. It was the drink that first helped humanity along the path to the modern world: beer.

Exactly when the first beer was brewed is not known. There was almost certainly no beer before 10,000 BCE, but it was widespread in the Near East by 4,000 BCE, when it appears in a pictogram from Mesopotamia, a region that corresponds with modern day Iraq, depicting two figures drinking beer through reed straws from a large pottery jar. (Ancient beer had grains, chaff, and other debris floating on its surface, so a straw was necessary to avoid swallowing them.) Beer is a liquid relic from human prehistory, and its origins are closely intertwined with the origins of civilization itself.

The Discovery

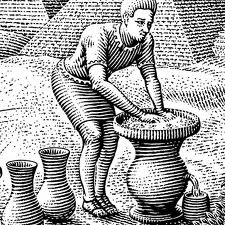

Beer was not invented but discovered. Once the gathering of wild grains became widespread, in a region known as the Fertile Crescent, people began to settle and build cities. The area stretches from modern day Egypt, up the Mediterranean coast to the southeast corner of Turkey, and then down again to the border between Iraq and Iran. When the ice age ended, the uplands of the region provided an ideal environment for wild sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs - and it permitted the wild growth of wheat and barley. Such grains provided a reliable source of food. They were unsuitable for consumption when raw, but they were pounded and crushed and soaked in water and cooked by placing the mash in a tightly woven basket and then heated stones were placed in the basket to make a sort of thick porridge or soup. Throughout the Fertile Crescent there is archaeological evidence from around 10,000 BCE of flint bladed sickles for harvesting cereal grains, woven baskets, stone hearths, underground pits, and grindstones for processing the grains.

Cereal grains took on greater significance following the discovery that they had two more unusual properties. The first was that grain soaked in water, so that it starts to sprout, tastes sweet. It was difficult to make storage pits perfectly water tight, so this property would have become apparent as soon as humans first began to store grain. The cause of sweetness is now understood: moistened grain produces diastase enzymes, which convert starch within the grain into maltose sugar, or malt.

The second discovery was even more momentous. Gruel or mash that was left sitting around for a couple of days underwent a mysterious transformation, particularly if it had been made with malted grain: It became slightly fizzy and pleasantly intoxicating, as the action of wild yeasts from the air fermented the sugar in the gruel into alcohol. The gruel, in short, turned into beer.

Once the crucial discovery of beer had been made, its quality was improved through trial and error. The more malted grain there is in the original gruel, for example, and the longer it is left to ferment, the stronger the beer. More malt means more sugar, and a longer fermentation means more of the sugar is turned into alcohol. Thoroughly cooking the gruel also contributes to the beers strength. The malting process converts only around 15 percent of the starch found in barley grains into sugar, but when malted barley is mixed with water and brought to the boil, starch-converting enzymes, which become active at higher temperatures, turn more of the sugar into sugar, so there is more of the sugar for the yeast to transform into alcohol.

Ancient brewers also noticed that using the same container repeatedly for brewing produced more reliable results. Repeated use of the same mash tub promoted successful fermentation because yeast cultures took up residence in the container's cracks and crevices, so that there was no need to rely on the more capricious wild yeast. Finally, adding berries, honey, spices, herbs, and other flavorings to the gruel altered the taste of the resulting beer in various ways. Over the next few thousand years, people discovered how to make a variety of beers of different strengths and flavors.

Since writing had not been invented at the time, there are no written records to attest to the social and ritual importance of beer in the Fertile Crescent during the new stone age, or neolithic period. But the first literate civilizations, the Sumerians of Mesopotamia and the ancient Egyptians considered beer very important for social and religious purposes. The ancients considered beer to have supernatural properties. Neolithic drinkers entertained the notion that beer had magical powers since it had the ability to intoxicate and induce a state of altered consciousness. Beer was considered a gift from the gods, and it was only logical to present the drink as a religious offering. The mysterious process of fermentation which transformed ordinary gruel into beer was attributed to the hand of god at work. Accordingly, many cultures have myths that explain how the gods invented beer and then showed humankind how to make it. The Egyptians believed that beer was accidentally discovered by Osiris, the god of agriculture and king of the afterlife. One day he prepared a mixture of water and sprouted grain, but forgot about it and left it in the sun. He later returned to find the gruel had fermented, decided to drink, and was so pleased with the result that he passed his knowledge on to humankind.

Since writing had not been invented at the time, there are no written records to attest to the social and ritual importance of beer in the Fertile Crescent during the new stone age, or neolithic period. But the first literate civilizations, the Sumerians of Mesopotamia and the ancient Egyptians considered beer very important for social and religious purposes. The ancients considered beer to have supernatural properties. Neolithic drinkers entertained the notion that beer had magical powers since it had the ability to intoxicate and induce a state of altered consciousness. Beer was considered a gift from the gods, and it was only logical to present the drink as a religious offering. The mysterious process of fermentation which transformed ordinary gruel into beer was attributed to the hand of god at work. Accordingly, many cultures have myths that explain how the gods invented beer and then showed humankind how to make it. The Egyptians believed that beer was accidentally discovered by Osiris, the god of agriculture and king of the afterlife. One day he prepared a mixture of water and sprouted grain, but forgot about it and left it in the sun. He later returned to find the gruel had fermented, decided to drink, and was so pleased with the result that he passed his knowledge on to humankind.

Beer was certainly used in religious ceremonies, agricultural fertility rites, and funerals, therefore the religious significance of beer seems to be common to every beer- drinking culture, whether in the Americas, Africa, or Eurasia. The Incas offered their beer called chicha, to the rising sun in a golden cup, and poured it on the ground or spat out their first mouthful a an offering to the gods of the Earth; the Aztecs offered their beer, called pulque, to Mayahuel, the goddess of fertility. In China, beers made from millet and rice were used in funerals and other ceremonies.

The best evidence of the importance of beer in prehistoric times is its extraordinary significance to the people of the first great civilizations.

References:

A History of the World in 6 Glasses by Tom Standage

© 2005 Walker & Company New York

References:

A History of the World in 6 Glasses by Tom Standage

© 2005 Walker & Company New York