|

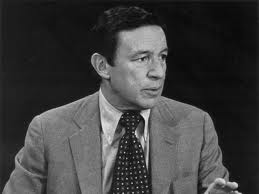

| Rod Serling, creator of The Twilight Zone |

Rodman Edward Serling was born in Syracuse, New York, on December 25, 1924, to a Reform Jewish family. After graduation from high school, Serling enlisted in the United States Army. The war and the army took a permanent mental toll; he would suffer from flashbacks, nightmares, and insomnia for the rest of his life. When discharged from the army in 1946 he was "bitter about everything and at loose ends."

Serling enrolled under the G.I. Bill of Rights at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. In the late 1940s Antioch was famous for loose social rules and a unique work-study curriculum. Serling was stimulated by the liberal intellectual environment and began to feel "the need to write, a kind of compulsion to get some of my thoughts down." A master writer was underway. He was also inspired by the words of Unitarian educator Horace Mann, first president of Antioch College, "Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity." Serling would later feature these words and a rendition of Antioch's Horace Mann statue in the 1962 Twilight Zone episode, "Changing of the Guard." His first writings were short stories, mostly about the war. In "Transcript of the Legal Proceedings in the Case of the Universe Versus War" a heavenly trial was conducted with Euripedes as prosecutor, Julius Caesar as lawyer for the defense, God as judge, and a jury of twelve angels.

By the late 1950s the days of the live New York teleplay were over and the television industry had begun to move to Hollywood, where there was more money, equipment and talent. In 1957 the Serlings moved to Pacific Palisades, California. Serling believed "that of all the media, TV lends itself most beautifully to presenting a controversy." He found that with television he could "take a part of the problem, and using a small number of people, get my point across."

However, Serling quickly realized that to get a point across often meant creating scripts that contained controversial messages and dialogues. Corporate sponsors, on the other hand, had no desire to have their products matched with messages that might be deemed offensive. In 1959 Serling expressed his frustration: "I think it is criminal that we are not permitted to make dramatic note of social evils that exist, of controversial themes as they are inherent in our society." Because of the hostile creative environment Serling began to see the advantages of writing science fiction and fantasy. He learned that advertisers would routinely approve stories including controversial situations if they took place on fictional worlds. Out of this realization came the television series The Twilight Zone, 1959-64, on which Serling and other writers would enjoy unprecedented artistic freedom.

|

| The Eye Of The Beholder (1960) |

In a rare and insightful interview (1959), Mike Wallace took an opportunity to ask questions to Rod Serling.

|

| The Mike Wallace Interview |

Mike Wallace: And now to our story with Rod Serling. Way back in 1951 when television was just a baby, a young man sat in a Cincinnati diner with his wife and came to a momentous decision. He decided to give up the security of his job and take a chance at becoming a free-lance television writer. Rod, first of all, let me ask you this. What was it that brought that decision about? Was it a burning desire to write because you felt that you had to say something or was it just a way to make more money?

Rod Serling: A combination of many things, Mike. The immediate motive at the time, the prodding thing that pushed me into it, was that I had been writing for a Cincinnati television station as a staff writer which is a particularly dreamless occupation composed of doing commercials, even making up...uh...letters of...what do they call it? To plug a product...somebody has used it...

Mike Wallace: Testimonial?

Rod Serling: Testimonial letters. As I recall, there was a drug, a liquid drug, on the market at the time that could cure everything from arthritis to a fractured pelvis, and I actually had to write testimonial letters. And on that particular day I had just had it, and though I had been free-lancing concurrent with the staff job—the best year I had ever had I think we netted about seven hundred dollars, which is hardly even grocery money. And that one night we just decided to sink or swim and go into it.

Mike Wallace: So you went, you came here to New York?

Rod Serling: Uh, not immediately. We stayed another six months, I guess, in Ohio then came to New York. Started principally in Lux Video Theatre, then live a half hour emanating from New York. I did eleven shows for them and I was sort of on my way from that point on.

Mike Wallace: And what kind of stuff did you write, because you said that it wasn't just the money. It was something that you wanted to say, that you weren't getting a chance to say in Cincinnati.

Rod Serling: Well, in those days, Lux Video, as one show, was doing reasonably adult stuff. These, of course, were not Playhouse 90s, nor were they award winning shows, but they were reasonably mature things that even today stand up pretty well. And I was doing Lux Video, Kraft Theatre, the early so-called pioneer days of television, which, of course, are hardly pioneer, but anything over eight years old is pioneer-style in television.

Mike Wallace: You worked a little for a television producer, David Suskind, at that time.

Rod Serling: I worked for David, yes.

Mike Wallace: You've come a long way since those early days, and perhaps more than any other writer, your name is figured in the classic battle, that is television writer, the battle of the writer to be his own man. What happens when a writer like yourself writes something that he really believes in, for television?

Rod Serling: I'm not sure I understand the question, Mike. What happens, you mean, in terms of...

Mike Wallace: Well, we hear a lot about censorship of the writer on TV, and a good deal about it in your own case especially.

Rod Serling: Well, depending, of course, on the dramatic treatment you're using, if you have the temerity to try to dramatize a theme that involves any particular social controversy currently extant, then you're in deep trouble.

Mike Wallace: For instance?

Rod Serling: Uh, a racial theme, for example. My case in point, I think, a show I did for the Steel Hour, some years ago—three years ago, called Noon on Doomsday, which was a story which purported to tell what was the aftermath, the alleged kidnapping in Mississippi of the Till boy, the young Chicago Negro. And I wrote the script using black and white, initially, then it was changed to suggest an unnamed foreigner. Then the locale was moved from the South to New England, and I'm convinced they'd have gone up to Alaska or the North Pole if, and using Eskimos as a possible minority, except I suppose the costume problem was a sufficient severity not to attempt it, but it became a lukewarm, eviscerated, emasculated kind of show.

Mike Wallace: You went along with it, though.

Rod Serling: All the way. I protested. I went down fighting, as most television writers do, thinking, in a strange, oblique, philosophical way that better say something than nothing. In this particular show, though, by the time they had finished taking Coca-Cola bottles off the set because the sponsor claimed that this had Southern connotations, suggesting to what depth they went to make this a clean, antiseptically, rigidly acceptable show. Why, it bore no relationship at all to what we had purported to say initially.

Mike Wallace: Paddy Chayefsky has talked about the insidious influence of what he called pre-censorship. How does that work?

Rod Serling: Pre-censorship is a practice, I think, of most television writers. I can't speak for all of them. This is the prior knowledge of the writer of those areas which are difficult to try to get through and so a writer will shy away from writing those things which he knows he's going to have trouble with on a sponsorial or an agency level. We practice it all the time. We just do not write those themes which we know are going to get into trouble.

Mike Wallace: Who's the culprit? Is it the network? The sponsor? It sure is not the FCC.

Rod Serling: No, it's certainly not the FCC, ideally speaking, of course. It's a combination of culprits in this case, Mike. It's partly network. It's principally agency and sponsor. In many ways I think it's the audience themselves.

Mike Wallace: How do you mean?

Rod Serling: Well, I'll give you an example. About a year ago, roughly eleven or twelve months ago, on the Lassie show—this is a story usually told by Sheldon Leonard who was then associated with the show—Lassie was having puppies. And I have two little girls, then aged five and three, who are greatly enamored with this beautiful Collie and they watched the show with great interest. And Lassie gave birth to puppies, and Mike, it was probably one of the most tasteful and delightful and warm things depicting what is this wondrous thing that is birth. And after this show, I think they were many congratulations all around because it was a lovely show, the sort of thing I'd love my kids to watch to show them what is the birth process and how marvelous it is. They got many, many cards and letters. Sample card, from the deep South this was: if I wanted my kids to watch sex shows, I wouldn't have them turn on that. I could take them to burlesque shows. And as a result of the influx of mail, many of the cards, incidentally as Sheldon tells it, were postmarked at identical moments all in the same handwriting, but each was counted as a singular piece of mail. And as a result, the directive went down that there would be no shows having anything to do with puppies, that is in the actual birth process. Well, obviously, it is this wild lunatic fringe of letter-writers that greatly affect what the sponsor has in mind.

Mike Wallace: You can understand the position of the sponsor, can't you?

Rod Serling: In many ways I suppose I can. He's there to push a product.

Mike Wallace: He has a considerable stake, thus, in what goes on the air.

Rod Serling: Most assuredly, and in those cases where there is a problem of public taste, in which there is a concern for eliciting negative response from a large mass of people, I can understand why the guys are frightened. I don't understand, Mike, for example, other evidences and instances of intrusion by sponsors. For example, on Playhouse 90, not a year ago, a lovely show called Judgment at Nuremberg, I think probably one of the most competently done and artistically done pieces that 90's done all year. In it, as you recall, mention was made of gas chambers and the line was deleted, cut off the soundtrack. And it mattered little to these guys that the gas involved in concentration camps was cyanide, which bore no resemblance, physical or otherwise, to the gas used in stoves. They cut the line.

Mike Wallace: Because the sponsor was...

Rod Serling: Did not want that awful association made between what was the horror and the misery of Nazi Germany with the nice chrome wonderfully antiseptically clean beautiful kitchen appliances that they were selling. Now this is an example of sponsor interference which is so beyond logic and which is so beyond taste—this I rebel against.

Mike Wallace: You've got a new series coming up called The Twilight Zone. You are writing, as well as acting executive producer on this one. Who controls the final product, you or the sponsor?

Rod Serling: We have what I think, at least theoretically, anyway, because it hasn't really been put into practice yet, a good working relationship, where in questions of taste and questions of the art form itself and questions of drama, I'm the judge, because this is my medium and I understand it. I'm a dramatist for television. This is the area I know. I've been trained for it. I've worked for it for twelve years, and the sponsor knows his product but he doesn't know mine. So when it comes to the commercials, I leave that up to him. When it comes to the story content, he leaves it up to me.

Mike Wallace: Has nothing been changed in the...

Rod Serling: We changed, in eighteen scripts, Mike, we have had one line changed, which, again, was a little ludicrous but of insufficient basic concern within the context of the story, not to put up a fight. On a bridge of a British ship, a sailor calls down to the galley and asks in my script for a pot of tea, because I believe that it's constitutionally acceptable in the British Navy to drink tea. One of my sponsors happens to sell instant coffee, and he took great umbrage, or at least minor umbrage anyway, with the idea of saying tea. Well, we had a couple of swings back and forth, nothing serious, and we decided we'd ask for a tray to be sent up to the bridge. But in eighteen scripts, that's the only conflict we've had.

Mike Wallace: Well...

Rod Serling: They passed...

Mike Wallace: They passed what?

Rod Serling: I mean, every script.

Mike Wallace: Is pre-censorship, though, involved? Are you simply writing easy?

Rod Serling: In this particular area, no, because we're dealing with a half hour show which cannot probe like a 90, which doesn't use scripts as vehicles of social criticism. These are strictly for entertainment.

Mike Wallace: These are potboilers.

Rod Serling: Oh, no. Un-uh. I wouldn't call them potboilers at all. No, these are very adult, I think, high-quality half hour, extremely polished films. But because they deal in the areas of fantasy and imagination and science-fiction and all of those things, there's no opportunity to cop a plea or chop an axe or anything.

Mike Wallace: Well, you're not gonna be able to cop a plea or chop an axe because you're going to be obviously working so hard on The Twilight Zone that in essence, for the time being and for the foreseeable future, you've given up on writing anything important for television, right?

Rod Serling: Yeah. Well, again, this is a semantic thing—important for television. I don't know. If by important you mean I'm not going to try to delve into current social problems dramatically, you're quite right. I'm not.

Mike Wallace: You told Kay Gardella of the New York Daily News this: you said "Professionally, I don't think Twilight Zone will hurt me, but I must admit I don't think it will help me either. I'm stepping out of the line of fire." You've had it as far as trying to beat your brains out.

Rod Serling: I have to lay claim to that being a misquote. I didn't state that, not verbatim. I didn't say that I was...would you just read me the first two lines, Mike?

Mike Wallace: "Professionally, I don't think Twilight Zone will hurt me, but I must admit I don't think it will help me either."

Rod Serling: I never said that. I'm convinced it'll help me. I have great pride in the show. In eleven or twelve years of writing, Mike, I can lay claim to at least this: I have never written beneath myself. I have never written anything that I didn't want my name attached to. I have probed deeper in some scripts and I've been more successful in some than others. But all of them that have been on, you know, I'll take my lick. They're mine and that's the way I wanted them.

Mike Wallace: But you're going to play fairly safe, let us say.

Rod Serling: No question about it.

Mike Wallace: Dave Suskind, on this program, had this to say. "Playing it safe," he said, "is a sure road to sterility and death." What about it?

Rod Serling: Well, of course, I've known David a long time. We've worked together. I think David sometimes has a kind of convenient lapse of memory in which he forgets the shows that he produced not too many years ago, which were safe shows in the extreme. Shows like Appointment With Adventure, that I wrote for. And these shows were, you know, cut off, sliced off the old ham. They were shows that, you know, characterized early television at the nadir of its mediocrity. I don't think playing it safe constitutes a retreat, necessarily. In other words, I don't think if, by playing safe he means we are not going to delve into controversy, then if that's what he means he's quite right. I'm not going to delve into controversy. Somebody asked me the other day if this means that I'm going to be a meek conformist, and my answer is no. I'm just acting the role of a tired non-conformist. And I don't wanna fight any more.

Mike Wallace: What do you mean you don't wanna fight any more?

Rod Serling: I don't wanna have to battle sponsors and agencies. I don't wanna have to push for something that I want and have to settle for second best. I don't wanna have to compromise all the time, which in essence is what the television writer does if he wants to put on controversial themes.

Mike Wallace: Well then why do you stay in television?

Rod Serling: I stay in television because I think it's very possible to perform a function of providing adult, meaningful, exciting, challenging drama without dealing in controversy necessarily. This, of course, Mike, is not the best of all possible worlds. I am not suggesting that this is at the absolute millennium. I think it's criminal that we're not permitted to make dramatic note of social evils as they exist, of controversial themes as they are inherent in our society. I think it's ridiculous that drama, which by its very nature should make a comment on those things that affect our daily lives, is in the position, at least in terms of television drama, of not being able to take this stand. But these are the facts of life. This is the way it exists, and they can't look to me or Chayefsky or Rose or Gore Vidal or J.P. Miller or any of these guys as the precipitators of the big change. It's not for us to do it.

Mike Wallace: Of course, Chayefsky got out of television.

Rod Serling: Yeah, he did, and I can't knock that. I think this takes a relative degree of guts to leave a medium that's made you, that made you sociable as kind of a household name. Paddy was the first guy to kind of lend stature to the television writer. Prior to Paddy Chayefsky, most of us were considered to be two-headed hacks who worked around the clock and used boy/girl situations and any one of five thousand different routine manners. But Paddy gave us a stature, and I respect Paddy's decision to leave. He felt that he wasn't satisfied with doing things half-best.

Mike Wallace: Do you think you could make it outside of television?

Rod Serling: Me? I'm not sure I could. And I suppose this is an admission of a kind of weakness or at least a sense of insecurity on my part. I've never had a Broadway play produced. What few motion pictures I've written have been somewhat less than spectacular. And I suppose I stay in the medium partly as an admission of I wanna stay in the womb. This is the medium I understand. These are the tools and techniques that I've been versed in for many years. Maybe I don't wanna get stuck up on the board and get shot at with darts on a Broadway play when I'm not sure I'm prepared for it. But Paddy was willing to take the chance. Gore Vidal writes novels. Bob Bartee did Broadway.

Mike Wallace: What about you and novels?

Rod Serling: Ultimately, I'd love to write a novel, and I think next year I'll start my play. Requiem was under option. It was written as a play, and I gave them their money back and I wanna do it over again. But I stay in the medium, also because I happen to like the medium.

Mike Wallace: Herb Brodkin, who was a TV producer who was associated with some of your earlier plays, has said this about you: he said "Rod is either going to stay commercial or become a discerning artist, but not both." Now, in just a second, I'd like to come back and have you talk to that. Are you going to stay commercial or become a discerning artist, and do you agree that you can't do both?

Mike Wallace: Rod, let me repeat it. Herbert Brodkin, a TV producer, associated with some of your earlier plays, has said this about you. He said, "Rod is either going to stay commercial or become a discerning artist, but not both." Now, has it ever occurred to you that you're selling yourself short by taking on a series which, by your own admission, is going to be a series primarily designed to entertain.

Rod Serling: I remember the quote. He gave it to Gilbert Millstein when Millstein was doing a profile on me in the New York Times. I didn't understand it at the time. I fail to achieve any degree of understanding in the ensuing years which are three in number. I presume Herb means that inherently you cannot be commercial and artistic. You cannot be commercial and quality. You cannot be commercial concurrent with have a preoccupation with the level of storytelling that you want to achieve. And this I have to reject. I think you can be, I don't think calling something commercial tags it with a kind of an odious suggestion that it stinks, that it's something raunchy to be ashamed of. I don't think if you say commercial means to be publicly acceptable, what's wrong with that? The essence of my argument, Mike, is that as long as you are not ashamed of anything you write if you're a writer, as long as you're not ashamed of anything you perform if you're an actor, and I'm not ashamed of doing a television series. I could have done probably thirty or forty film series over the past five years. I presume at least I've turned down that many with great guarantees of cash, with great guarantees of financial security, but I've turned them down because I didn't like them. I did not think they were quality, and God knows they were commercial. But I think innate in what Herb says is the suggestion made by many people that you can't have public acceptance and still be artistic. And, as I said, I have to reject that.

Mike Wallace: One of your most recent plays was one called The Velvet Alley, right?

Rod Serling: Right.

Mike Wallace: It was about the corrupting influences of Hollywood and big money.

Rod Serling: Right.

Mike Wallace: Where'd that come from? Your own experiences?

Rod Serling: Many, part of it was very autobiographical, part of it was a composite of observation of other people involved.

Mike Wallace: Well, what do you mean by the corrupting influence of Hollywood and big money? What is that all saying?

Rod Serling: Well, I didn't mean to suggest that corruption had a geographical tag, that it was necessarily the corruption of Hollywood. What I tried to suggest dramatically was that when you get into the big money, particularly in the kind of detonating, exciting, explosive, overnight way that our industry permits, there are certain blandishments that a guy can succumb to and many do.

Mike Wallace: Such as?

Rod Serling: A preoccupation with status, with the symbols of status, with the heated swimming pool that's ten feet longer than the neighbors, with the big car, with the concern about billing, all these things. In a sense rather minute things, really, in context, but that become disproportionately large in a guy's mind.

Mike Wallace: And because those become so large, what becomes small?

Rod Serling: I think probably the really valuable things, and I know this sounds corny and sorta Buckwheat-ish to say things like having a family, being concerned with raising children, being concerned with where they go to school, being concerned with a good marital relationship. All these things I think are of the essence. Unfortunately, and the problem as I tried to dramatize in The Velvet Alley, was that the guy who makes the success is immediately assailed by everybody, and you suddenly find yourself having to compromise along the line, giving so many hours to work and a disproportionate number of fewer hours to family, and this in inherent in our business.

Mike Wallace: How many hours a day do you work right now as executive producer and/or writer on...

Rod Serling: Twelve to fourteen hours a day.

Mike Wallace: How many days a week?

Rod Serling: Seven.

Mike Wallace: I don't mean, now seriously, I'm not asking for figures here, but obviously The Twilight Zone is your own creation. You're doing it for money. I think that our audience would be fascinated to know, and again I don't want to get too specific, but how rich can a fellow get under these circumstances?

Rod Serling: Well, if the show is successful, he can get tremendously rich. He can make a half a million dollars, I suppose.

Mike Wallace: Half a million dollars a what? A year?

Rod Serling: Over a period of three or four years, I suppose. But, Mike, again this sounds defensive and it probably sounds phony, but I'm not nearly as concerned with the money to be made on this show as I am with the quality of it and I can prove that. I have a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer which guarantees me something in the neighborhood of a quarter of a million dollars over a period of three years. This is a contract I'm trying to break and get out of, so I can devote time to a series which is very iffy, which is a very problematical thing. It's only guaranteed twenty-six weeks and if it only goes twenty-six weeks and stops, I'll have lost a great deal of money. But I would rather take the chance and do something I like, something I'm familiar with, something that has a built-in challenge to it.

Mike Wallace: But it's even possible, though, that if it is a success, you could make well over the two million dollars that you suggested—four years at half a million apiece.

Rod Serling: Quite right, but I happen to feel, after a year and a half of working twelve to fourteen hours a day, it's worth it. And I think I rate it. I think anybody does who works that hard and can create an idea and can make a show go.

Mike Wallace: Let's come back to something that David Suskind said, not about you this time. He said this about network programming. We have only about three minutes to do this. He said, "ABC is western, mystery quiz and Lawrence Welk from top to bottom and represents television at its worst. And NBC seems to be trying to catch them at their own game." He felt somewhat better about CBS. How do you rate the three networks?

Rod Serling: I have to have a kind of, almost a proprietary feeling towards CBS because they've been better to me and better to most writers than any network.

Mike Wallace: Why?

Rod Serling: CBS was the only network who hired writers under contract, who gave us this kind of free-wheeling, to write as we wanted to write. A chance to write, an avenue, a channel through which we could write. They put on a Playhouse 90, which lost them a great deal of money and kept it on three years and will continue to produce it. I've had not nearly the experience—I've have no experience with ABC except one minor hour show five, six years ago.

Mike Wallace: I know, but you see their shows from time to time, in spite of your twelve to fourteen hour daily schedule.

Rod Serling: I'm afraid I would probably have to go along with David on that. But of the three networks I think CBS has the edge. However, I think NBC runs awfully close. It's almost which paper do you read. They've got this NBC showcase coming on. Now, ABC I'm not quite as familiar with.

Mike Wallace: Is television good?

Rod Serling: Some television's wonderful. Some television is exciting and promising and has vast potential. Some television is mediocre and bad. But I think it has promise, Mike. I think this conceivably can be a real art form. And I stick with it for the reasons I said and because I think it can only improve and can improve tremendously and I think aims toward that.

Mike Wallace: One minute. Can pay television make any difference?

Rod Serling: I've never quite understood pay television. I rather think not. If it's there, substantially to fix the evils that presently exist, I think the same things will apply. They'll put on the stuff that they thing the greater number of people want. A totally quantitative view of things.

Mike Wallace: You don't think that perhaps be able to play to a more perceptive audience?

Rod Serling: I doubt it.

Mike Wallace: A smaller audience for special things?

Rod Serling: No, because it's still governed by the buck, and I think they'll play what they think will garner the most bucks.

Mike Wallace: There can't be small pay television producers who won't be governed, necessarily, by the buck?

Rod Serling: I'd like to see them come out. I'd welcome it.

Mike Wallace: Thirty seconds. What would you most like to write?

Rod Serling: A good, legitimate play, having to do with the McCarthy era in television.

Mike Wallace: I hope we'll see it. Rod Serling, thanks very much...

Rod Serling: Thank you, Mike.

Mike Wallace: Rod Serling's story can be summed up in just a few words. From forty rejection slips to three Emmy awards. From a trailer home to a hacienda in Hollywood complete with swimming pool. It hasn't been a long road, but it's been a hard one, and the last couple of miles have been paved with gold. We thank Rod Serling for adding his portrait to our gallery. One of the people other people are interested in. Mike Wallace, that's it for now.